NYSUT President Dick Iannuzzi sat down for a conversation with Peter Edelman, a leading antipoverty advocate and author of a provocative new book, So Rich, So Poor, Why It's So Hard to End Poverty in America.

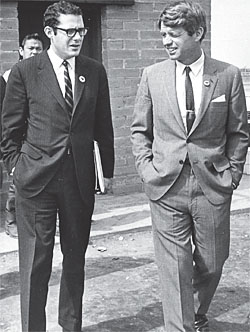

Edelman, a top adviser to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in the 1960s, is now a professor at Georgetown University Law Center. Iannuzzi and Edelman met through their work with the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights.

Edelman, a top adviser to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in the 1960s, is now a professor at Georgetown University Law Center. Iannuzzi and Edelman met through their work with the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights.

Dick Iannuzzi: I've read your book and I'm in the middle of reading [Joseph] Stiglitz's book [Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future]. I saw Robert Reich's movie ["Inequality For All"]. Why the renewed interest in poverty and inequity?

Peter Edelman: The number of people in poverty has shot up since the beginning of this new century. When Bill Clinton left office, we had 31 million people in poverty and we now have 46 million … that has turned some heads.

The other thing that has become so dramatically more visible is the incredible inequality we have in this country. Those numbers have widened over the last few years. And then Occupy came along. It didn't last very long, but it had a good effect in calling people's attention to the enormous gulf between the top and the bottom. It's a little bit paradoxical because there's probably less political interest nationally in doing something about it now than there has been for a very long time.

DI: You mention preschool, community schools and community colleges in your book as fundamental concepts when it comes to beating the cycle of poverty.

PE: It starts at the beginning, and we know now more than ever the science of brain development for children and what's lost if they come to school not ready.

The challenge to teachers is very dependent on the children coming from families that are in good shape and, of course, having had breakfast. That's where community schools come in.

One of my very strong views is that we are not doing enough, starting in high school, to create pathways that lead to good jobs. We must build career and technical education. The jobs of the 21st century require post-secondary education, but not necessarily a two- or four-year degree — sometimes what's needed is some type of certificate through the community college.

DI: You make a great point in the book that we can't just focus on trying to increase the number of high school graduates. We need to be reconnecting with those who drop out.

PE: It's somewhat reciprocal because we need to hold the maximum in school, and we are not doing that. There are a lot of reasons. One is that high school doesn't hold their interest. We need to reform our criminal justice system because it's scooping up far too many people and leaving them with so little opportunity once they try to come back into the community. We must invest in those who need a second chance.

DI: I think that makes great sense. The issue is whether there really is the political will to take those kinds of steps.

PE: I think political will is fundamental to all of this.

DI: Let me take you back … you had a great history with Robert F. Kennedy. He had this keen understanding of the need to focus on poverty and he did it not only in an urban setting like Bedford-Stuyvesant, he did the same in a rural setting in Appalachia. What lessons may be there for us today?

PE: He was absolutely committed to children everywhere. [We] visited children and their families in rural places all over the country, not just Appalachia but in the Mississippi Delta and on Indian reservations, upstate New York, many places.

The urban question is so hard; the rural question is even harder because it's just not very likely that economic development is going to take place there. We have to find a way to at least create more income for their families. Objectively, it's difficult to have to say it, but kids have to be enabled to get out, to go to places where there are jobs. We don't really have an on-the-shelf strategy of economic development for rural areas and it's continuing since Robert Kennedy's time. It's a very, very hard set of questions. We have to keep at it.

DI: You speak of public partnerships and the role of government. For most citizens, government has almost become a bad word. Is government really willing to pick up this challenge?

PE: Right now it is discouraging; the people who are a pretty small minority in our country have found a way to put themselves into disproportionate power in the decision making in Washington. Unfortunately, gerrymandering has left them in a position where it's somewhat hard to see when the malapportionment will go away.

The very tiny sort of silver lining in this huge awful black cloud is that people are getting more and more sick of this — even to the point where in 2014, they'll kick some of these people out. The demographics in our country are changing. It's a fact that's already in place and if people become active politically, they can make a difference in who's in power at all levels in the country.

DI: You used a phrase in your book that is very optimistic — that the "weapon of mass construction" is us. We know it's in our self interest to move this conversation forward. We realize those who see themselves in the middle have more in sync with those who are less fortunate than with those who are at the top.

PE: We just need every messenger and, of course, unions have to play a great role in that.

DI: In both education and health care, the real challenge again is that fringe element. In education we have the fringe that says everything about Common Core is terrible and in health care we have the fringe that says Obamacare has to go. In a lot of ways, it may very well play into the very things that keep the wealth gap growing.

PE: Yes, that's all absolutely true. This is a struggle that is going to continue. My tempered optimism is that, as the electorate changes in its composition, we'll see results that reflect what they do when they go to vote.

DI: In your book you speak about what you called a "false dichotomy" between those who think poor children will never learn unless we deal with the baggage of poverty and, on the other hand, those who take the exact opposite position, which is it's not poverty — they can do it with boot straps.

PE: We just can't create the maximum possibilities for children growing up and being fully included in the society and in the economy if we don't do something about their growing up in poverty. Everything tells us that children who grow up in poverty are much more likely to be adults in poverty.

There is this argument by some people who seem to say that if we make the schools perfect, then that will be it. All kids will go through and be able to get to a better position than their parents were in. It's a way of saying to the teachers we are not going to let you off the hook. The fact is you can have the most wonderful school and if kids are poor, only a fraction of them will get the full benefit from that. If something isn't done about the economics and the efficacy of the family, many kids will get lost.

DI: As teachers, we try hard to make clear that the conversation about poverty is not meant to be an excuse, rather just a reality; that this is one of the factors that teachers have to deal with.

PE: There are only 24 hours in the day, so not everybody can do everything. But to the extent that people who are on the school side of education, their position on poverty is: Well, we will have the school breakfast program, and we'll have a clinic in the school, and we'll have some social services in the school — that's the end of the responsibility. There must be even more — a coalition that's talking about jobs, family supports, building the healthier communities.

DI: In your New York Times op ed, you said, "History shows us that people power wins sometimes." Do you think this is potentially one of those times?

PE: We have to think that. Of course, what are our choices about any of this? It's absurd to say, "It's hard so I am going to quit." Not allowed! It's not a choice that's available because the bad interests and the bad outcomes are certainly going to prevail if people aren't fighting about it … The fact is the self interests and what ought to be done are aligned, but people aren't seeing it.