While textile mills and collar laundries were an important part of the Industrial Revolution, the underpaid, overworked women who toiled in factories choked with cotton dust and steam-filled, bleach-ridden commercial laundry rooms knew they had to fight for change.

The women who stepped up and put their jobs in peril during rough economic times changed the face of labor. They were the first women in the country to organize; to form unions; to strike and petition. They gathered their brave sisters in walkouts and with testimony about unsafe working conditions. Here are a few of the stories of the many women who led, and who encouraged thousands of others to speak their truth.

Sarah Bagley and the Lowell Factory Labor Reform Association

Imagine working so many hours that after decades of effort a 10-hour workday was a great victory.

The textile industry was on the rise in the 1830s, and so was the hiring of women to work the looms. In fact, young, single women were actively recruited to places like Lowell, Mass., where many factories sprouted up as industry rose above agriculture. Despite promises of favorable working conditions, the thousands of women working in the mills were subjected to low wages and rent increases in the factory housing where they lived, all while working 12-14 hour days in factories clogged with cotton dust and smoke from oil lamps.

Workers formed the Lowell Factory Labor Reform Association to stand up for better working conditions. In 1845, textile worker Sarah Bagley, who worked as a weaver and then a dresser, was named the first president. The group used petitions, strikes and testimony before the state legislature to try to turn around the industry, though they met with much resistance and did not find quick success. It was the first organization of women to come together and bargain collectively.

In 1847 the mills shortened the workday by 30 minutes; then to 11 hours in 1853. It wasn’t until 1874 that the Massachusetts legislature adopted the 10-hour workday law.

Bagley and her peers approached reform from other angles as well. The New England Historical Society reports that the LFLRA bought a printing press so it could publish its own labor newspaper, “The Voice of Industry.” This was an important strategy, since the local newspaper, “The Lowell Offering,” had been purchased by a friend of the employer and would no longer run articles criticizing the factories. With their own publication, the workers could get the word out about what was really happening behind the factory doors.

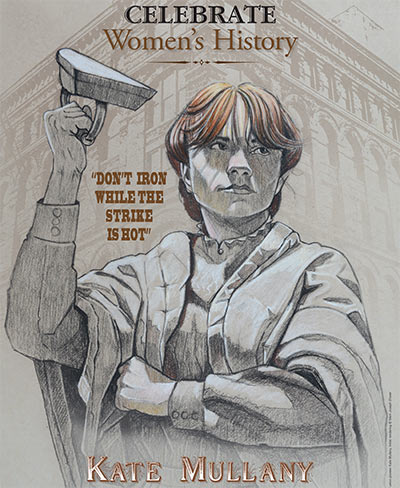

Kate Mullany

When new starching machines began burning women working in the collar laundry in Troy, N.Y., young Kate Mullany knew she had to take action – even at the risk of losing her job, which supported her widowed mother and siblings. Already, women worked up to 14 hours a day in the laundry, washing with soap and bleaching with chloride of soda and sulfuric acid to whiten the detachable collars. They boiled, rubbed and rinsed; starched, dried and ironed. Their hands were immersed in boiling hot water, bleaches and soap. Irons burned many of the workers.

In 1864, Mullany mustered with Esther Keegan to form the first women’s union in the country, the Collar Laundry Union. Three hundred women from 14 laundries went on strike that winter, walking in the cold for five and a half days in demand for a 25 percent wage increase and precautions against the scalding starching machines. This strike, and several more following, won wage gains for the women.

The Collar Laundry Union also stepped quickly into solidarity and social justice, a hallmark of labor unions, by donating to the molders during their Great Lock-Out, and later to the bricklayers. Mullany was appointed assistant secretary of the National Labor Congress, marking the first time a woman had held that role.

In 1869, Mullany purchased a home in Troy, a brick, double row house, for herself, her mother and siblings, an incredible feat for a woman and an Irish immigrant. The home is now a National Historic Site and is being restored by the American Labor Studies Center.

The Collar Laundry Union did not weather the test of time as well as the home. Working with the collar manufacturers, the laundry owners refused to negotiate further wage increases and the manufacturers would not send more collars and cuffs to laundries employing unionized workers. Mullany helped start their own business, the Union Line Collar and Manufactory, but the manufacturers switched to paper collars.

The union was dissolved, although many women continued to be part of a network of women labor activists.

Women’s Trade Union League

One can imagine, with women having no right to vote, no political power, and few legal rights, how difficult it would be to establish safe, fairly paid work for women. Activists formed the Women’s Trade Union League in 1903 as the first national association devoted to organizing women workers.

Labor leaders Mary Kenney O’Sullivan and Leonora O’Reilly, along with settlement workers Lillian Wald and Jane Addams, created the league of activists after the American Federation of Labor closed ranks and left out women. They wanted to see women have educational opportunities as well as safe places to work.

Their causes were many and timely: They spoke out against women working at night and child labor, and in favor of a minimum wage. They helped striking garment workers – most notably the workers in the massive New York Shirtwaist Strike of 1909 – also known as the “Uprising of the 20,000.” It was the largest strike by female American workers up to that date, led by Clara Lemlich and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union.

The WTUL also worked on long and difficult cases. After the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, they conducted a four-year investigation of factory conditions to help establish new regulations.

The league brought an interesting perspective because its members included working women, middle class women and wealthy women. It remained in existence until 1950.