In Nevada, the teacher shortage is so acute the superintendent launched a “Calling All Heroes” recruitment campaign by dressing up as Clark Kent and zip-lining over a street in downtown Las Vegas. In California, lawmakers are considering giving teachers a series of tax breaks, including a state income tax exemption, if they remain in the profession more than five years. In the Midwest, districts are putting up billboards in neighboring states and offering hiring bonuses to entice out-of-state teacher applicants.

In Nevada, the teacher shortage is so acute the superintendent launched a “Calling All Heroes” recruitment campaign by dressing up as Clark Kent and zip-lining over a street in downtown Las Vegas. In California, lawmakers are considering giving teachers a series of tax breaks, including a state income tax exemption, if they remain in the profession more than five years. In the Midwest, districts are putting up billboards in neighboring states and offering hiring bonuses to entice out-of-state teacher applicants.

Here in New York, the situation is not yet that dire, but the storm clouds are swirling.

As baby boomer teachers retire, and more and more teachers leave the profession for other reasons, enrollments in teacher education programs are plummeting.

What do you think? We want to hear from you: What are the best ways to bring in and support the next generation of teachers? Do you have existing programs in your districts or colleges to support teacher recruitment, preparation and retention? How can the union partner with you and your students to encourage them to go into the profession? What would you say to encourage future teachers? Go to www.nysut.org/futureteachers to submit comments, or post on our Facebook page — www.facebook.com/NYSUTUnited.

The ominous numbers, included in a new fact sheet prepared by NYSUT’s Research and Educational Services, are telling:

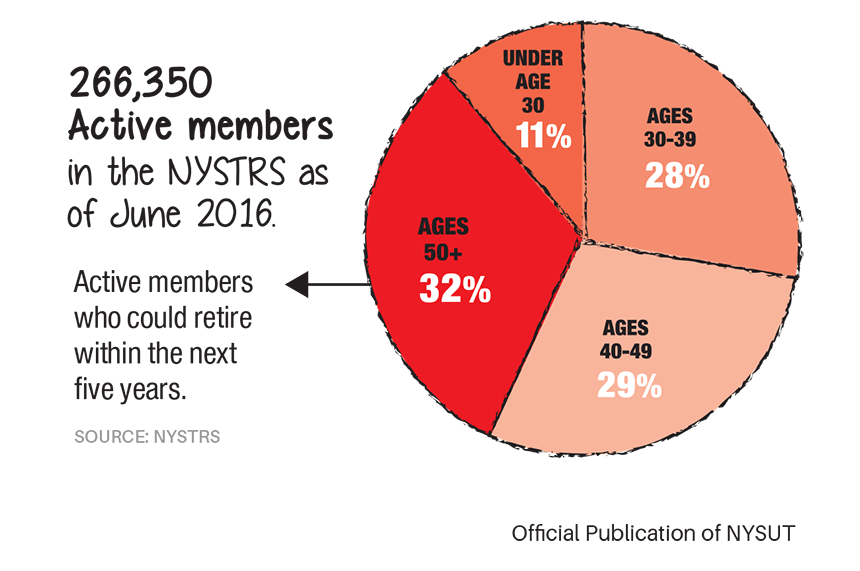

- More than 50,000 active State Teachers’ Retirement System members are older than 55, according to the 2016 NYSTRS annual report. Within the next five years, TRS projects more than one-third of the nearly 270,000 active members could be eligible to retire.

- The average age of teachers in the state is 48.

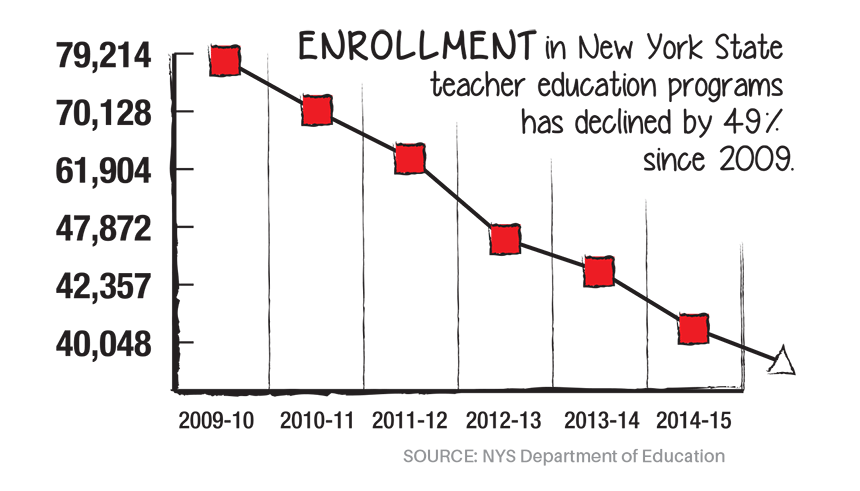

- Since 2009–10, enrollment in teacher education programs in New York has decreased by roughly 49 percent — from more than 79,000 students to about 40,000 students in 2014–15. Anecdotally, teacher education programs report those numbers have declined further in the last two years.

- An estimated 10 percent of New York teacher education graduates are leaving the state for employment elsewhere, with many blaming the state’s cumbersome certification system.

- Eleven percent of New York teachers leave their school or profession annually, according to a recent report by the Learning Policy Institute. Those numbers go up for early career teachers and those working in high-poverty areas. About 55 percent cited professional frustrations, including standardized testing, administrators or too little autonomy. About 18 percent cited financial reasons and job insecurity, according to LPI.

- The U.S. Department of Education estimates that 1.6 million new teachers will be needed nationally between 2012 and 2022; LPI estimates the nation will need about 300,000 new teachers per year by 2020.

- SUNY Chancellor Nancy Zimpher predicts New York will need more than 180,000 new teachers in the next decade. Aside from filling the thousands of vacant positions, many districts are looking to restore teacher positions and programs that were cut during the Great Recession. A New York State School Boards Association analysis found that the number of public school teachers decreased by nearly 11 percent from 2006–07 to 2014–15.

- At the same time, the federal government projects New York‘s student enrollment will grow by 2 percent by 2024, with high-need school districts experiencing the largest increases.

“When you look at all these numbers together, it’s really the perfect storm for an upcoming teacher shortage crisis,” said NYSUT Executive Vice President Jolene DiBrango, who oversees NYSUT’s Research and Educational Services Department. “We need to raise awareness on the issue — and work with higher ed and others to attract more students and adults to the profession.”

At a meeting this spring with NYSUT local leaders, State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia said finding ways to recruit and retain teachers must be front and center.

In many parts of the state, the shortage is already manifesting:

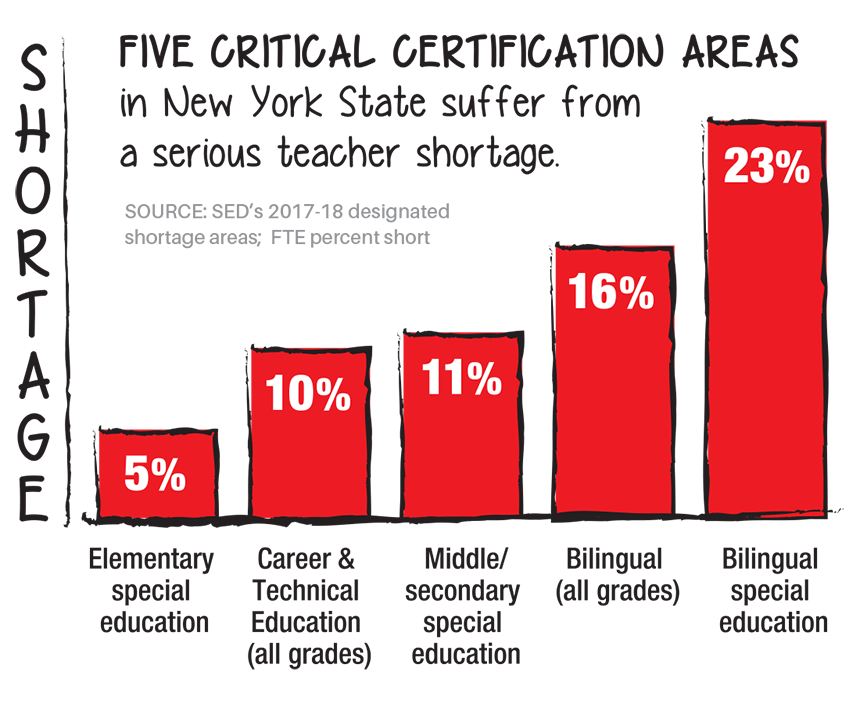

In November 2013, SED reported the following statewide teacher shortage areas between 2010 and 2014: bilingual education, chemistry, CTE, earth science, English language learners, Languages other than English, library and school media specialist, physics, special education, special education – bilingual, special education – science certification, and technology education. In New York City, SED identified shortage areas that include the arts, biology, chemistry, CTE, English, health education, library media specialist and mathematics.

SED’s “Teacher Supply and Demand Report,” has not been updated since 2013 . However, anecdotal evidence shows New York’s current teacher shortages are hitting urban and rural districts the hardest.

In big city districts, too many newly hired teachers are leaving out of frustration or for higher-paying jobs in the suburbs. “In exit interviews, these educators cited a variety of reasons, but first and foremost, they found the difficult working conditions and lack of support too overwhelming,” said Karen Alford, vice president of elementary education for the United Federation of Teachers.

Rural districts are also having a tough time recruiting and retaining staff. It used to be that local SUNY colleges provided a steady pipeline, but that’s not the case anymore — especially for high-need subject areas.

At a meeting with Assemblywoman Addie Jenne, D-Theresa, North Country leaders lamented that undergraduate education majors at SUNY Potsdam numbered only 216 in fall 2016 compared to 729 undergrad education majors in 2010.

“One of my biggest frustrations right now is we have already been contacted about a dozen (local) openings for math teachers and we are only going to have three [math] graduates this year,” said SUNY Potsdam Secondary Education Department Chair Peter Brouwer, a member of United University Professions at SUNY Potsdam.

Working with K–12 members, UUP at SUNY and the Professional Staff Congress at CUNY, NYSUT is developing a long-term campaign to raise awareness about the issue and offer solutions. For example, research has shown that strong support for beginning teachers can reduce a teacher’s odds of leaving the profession in the first year from 41 percent to 18 percent, DiBrango said. This could include mentoring programs, shared planning time and resources, such as a teacher aide or teaching assistant.

In a major win for union and higher education activists earlier this spring, the Regents approved significant changes to begin fixing the state’s new teacher certification process, which was discouraging many students from entering the profession.

The Regents eliminated one of four certification exams and called for further study of a new review process to help candidates successfully complete the edTPA, and creation of a clinical practice work- group to review the length and requirements of student teaching.

“Our work on the teacher certification process shows what can happen when we speak out and advance solutions that are fair and make sense,” DiBrango said. “We need to do everything we can to demonstrate what an incredibly rewarding profession teaching is and that those who make it their life’s work will never regret it.”

Removing roadblocks on the path to teaching

NYSUT is committed to advancing solutions to the state’s looming teacher shortage — a complex problem that requires comprehensive remedies.

“We are developing what will be a long-term campaign that will attract bright, talented, dedicated students and adults to the profession,” said NYSUT Executive Vice President Jolene DiBrango. “As a teacher, I can say with confidence that we enter our profession inspired by a love for what we do. That hasn’t changed. But the next generation faces unprecedented roadblocks on the path to teaching. NYSUT has made progress in tackling some of these road blocks — yet more needs to be done.”

Working with United University Professions and the Professional Staff Congress, NYSUT’s higher education affiliates, the statewide union spearheaded recent improvements to the teacher certification process. Similarly, the union’s success in standing up to the state’s “test-and-punish” approach to teacher evaluations has improved the climate for teaching and learning, but much work remains.

DiBrango said the union’s research arm is developing a statewide inventory of district and campus programs with proven success in recruiting, preparing and retaining teachers.

“There are many strong programs for mentoring and providing ongoing support to future teachers, but in too many cases they are starved of resources,” DiBrango said.

Jamie Dangler, vice president for academics of UUP, NYSUT’s affiliate at SUNY, agrees: “SUNY has many quality programs — developed in collaboration with local districts and dedicated to mentoring teachers — but a lack of resources limits their reach.”

In a recent meeting with leaders of the Syracuse TA, DiBrango embarked on what will be continuing conversations across the state with members and leaders on educational issues, including the teacher shortage.

Syracuse TA President Megan Root said the shortage is already on many districts’ doorsteps.

“We have had a hard time recruiting,” Root said. Strategies to attract and keep staff include an improvement in starting salary and an urban fellowship program that holds great promise for teacher retention.

“NYSUT is launching our campaign for the long haul,” DiBrango said. “We know we can’t solve this problem alone, and we know we’re not alone in this work. Together with our locals, we’ll identify and advance ways to encourage kids to go into the profession and help them along the way.”